|

|

|

|

These pages are for serious music listeners and are best viewed on a desktop, a laptop or a tablet.

|

Warning:

Thanks to hosting company ARVIXE, my pages on soundfountain.com are in disarray. Arvixe moved the server from Texas to Provo, Utah without warning and without providing the necessary codes, password and server address, while the yearly payment had been made and acknowledged by Arvixe for the period until October 2023. We certainly hope that the inconvenience to you, the visitor, will gradually end as the pages are now hosted in the Netherlands. |

|

Research,

scans of original images, Rudolf A. Bruil.

On the afternoon of Saturday, 24th of January, 1953, a special presentation was held for the Dutch press and important members of the musical and commercial scene in the Netherlands. They gathered in the so called 'Kleine Zaal' (small auditorium) of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam.

There was an important announcement to be made. Yet no instrumentalist and no singer was present on the stage to add to the importance of the gathering. What could be seen was a catafalque surrounded by flowers. And there was a somber painting - in the style of Dutch painter Jan Toorop - hanging in the background, as journalist Ruth Zimmerman described it in Dutch weekly 'Vrij Nederland'. It all looked as if a funeral service was going to take place. No wonder there was a cold and dull expression on most faces. Until... ... until the murmur of people in a large acoustic space was being heard through loudspeakers... the catafalque apparently hid a sound reproducing system. The murmur was followed by a firm, light ticking of a baton, the conductor's baton, not just calling all musicians to be attentive, but merely asking the audience to be quiet. And then the performance began, in fact the performance of Johann Sebastian Bach's 'Matthaeus Passion' by soloists, Toonkunstkoor, Boys' Choir `Zanglust' led by Willem Hespe, (Royal) Concertgebouw Orchestra and conductor Willem Mengelberg, exactly as it had been recorded on April 2nd, Palm Sunday, 1939! The music came from four twelve inch Philips Minigroove Long Playing records.

Many

a journalist reported that from the first bar until the last, everyone

present on that Saturday, was captivated by the extraordinary performance

of Bach's 'St. Matthew Passion', now played back from four Philips

Minigroove Long Playing Records with a total playing time of three

hours, notwithstanding the cuts Mengelberg had made.

The headline of journalist Ruth Zimmerman's column read: 'One cannot describe happiness', thus indicating the impact the auditioning had on her and on others present. She writes that for the first time she understood the full impact of the text "Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden, so scheide nicht von mir." (When once I must depart, Do not depart from me.)

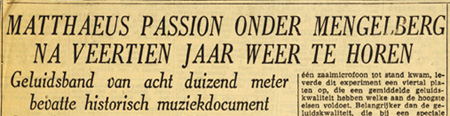

Under the heading 'Matthew Passion under Mengelberg heard again after 14 years' Dutch music critic and reviewer Ralph N. Degens wrote in his review about the 8000 meter sound recording which had been transferred to LP:

"(...)

Philips Eindhoven was in the posession of a registration of this performance

on a so called Miller Tape. This sound tape with a total length of eight

kilometer, was handed over to Philips' Phonographische Industrie

in Baarn, wanting to try to transfer the sound of this film to long

playing records. (...)

In 1939, Hungarian alto Ilona Durigo was 57 years of age. Tenor Karl Erb (1877-1958) was 62. He sang in Mengelberg's Matthaeus Passion every year from 1918 on and would do so for the last time in 1943.

Mengelberg

himself was 68. Violinist Louis Zimmermann, born in 1873 in Groningen,

had been concert master of the Concertgebouw Orchestra since 1911. He

played the violin solos. His violin was a Guarneri del Gesu. He was

65 years of age. Violinist Ferdinand Helmann (1880-1954) who

played in the orchestra from 1916 till 1948, was 59 years. His violin

was a Gagliano.

They all were artists who were recognized and celebrated by the devoted music listeners and concert goers. Jo Vincent, Louis van Tulder, and violinist Louis Zimmerman, were popular in the musical circles around the country. They recorded for Columbia Records. Above is an advertisement which appeared in Dutch weekly 'Panorama' of December of 1936 announcing 'Our Christmas Program'.

The youngest performer of importance in the 1939 Mengelberg recording was organist Piet van Egmond, who had started his career as organist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra when he was only 19 years old, now aged 27. In

the mid nineteen fifties Piet van Egmond himself conducted a complete

performance of Bach's St. Matthew Passion for the Musical Masterpiece

Society label with Corry Bijster (soprano), Annie Delorie (alto), Willy

van Hese (tenor), and Carel Willink (bass). Instrumentalists

were Koen van Slogteren (oboe da caccia), Leo van der Lek (oboe d'amore),

Willy (Wilhelm) Busch (violin), Piet Lenz (viola da gamba), H. Sekrève

(violoncello), Hans Philips (cembalo), Alex Schellevis (organ), the

Amsterdam Oratorio Choir, the Vredescholen Boys Choir, and the Rotterdam

Chamber Orchestra (selected members of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra).

The

recording was made in the Old Church (Oude Kerk) in Amsterdam, in 1955,

and released on The Opera Society / Concert Hall / Musical Masterpiece

Society label, reference MMS 2037, 3x 12" LP.

It

was Mengelberg, born March 29, 1871, in Utrecht, the Netherlands, who

established the tradition of performing Bach's St. Matthew Passion BWV

244, every year, for the first time on April 8, 1899. Like Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy,

the discoverer of the original SMP score, Mengelberg made also several

cuts; for whatever reason.

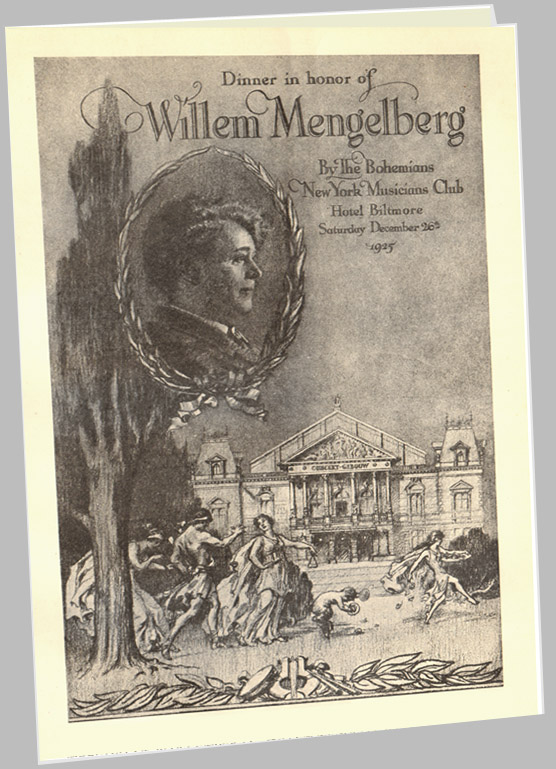

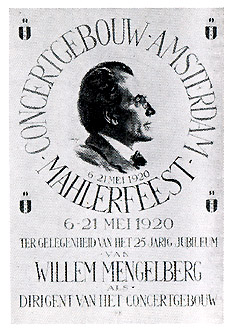

Mengelberg was conductor in New York from 1921 till 1930. First of the National Symphony Orchestra and from 1922 on of the New York Philharmonic Society (after these two orchestras had merged). On December 26, 1925, Willem Mengelberg was honored during a Dinner organized by "The Bohemians, New York Musicians' Club". American composer Rubin Goldmark (1872-1936) said in his honoring speech:

The

Concertgebouw of Amsterdam at the time when Willem Mengelberg was a

revered conductor in New York.

Rubin Goldmark surely used the meaning of "faithful" in a pure musicological sense. In her interesting and amusing memoirs, "Singing Through Life" (Zingend door het leven), published in 1960, soprano Jo Vincent mentions the musicological aspect of Mengelberg's interpretation of Bach's St. Matthew Passion:

Naarden being the town where, from 1931 on, the Dutch Bach Society (Nederlandse Bach Vereninging) led by Dr. Anton van der Horst gave a more authentic rendering of Bach's masterpiece of which a recording from the 1957 performance exists on Dutch Telefunken /CNR LCT 8002/5, with the Residency Orchestra (Hague Philharmonic Orchestra) and Dutch singers - Tom Brand (tenor), Laurens Bogtman (bass), Guus Hoekman (bass), Erna Spoorenberg (soprano), Annie Hermes (contralto), Arjan Blanken (tenor) - and many well known instrumentalists: violinists Herman Krebbers and Theo Olof, viola da gamba player Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp, oboist Constant Stotijn, organist Albert de Klerk,and cellist Martin Zagwijn.

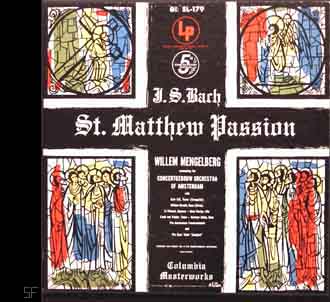

When

American Columbia had made the complete Mengelberg SMP Philips recording

available in the US in the fall of 1953, critic

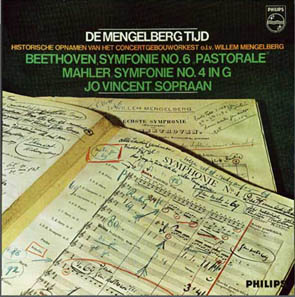

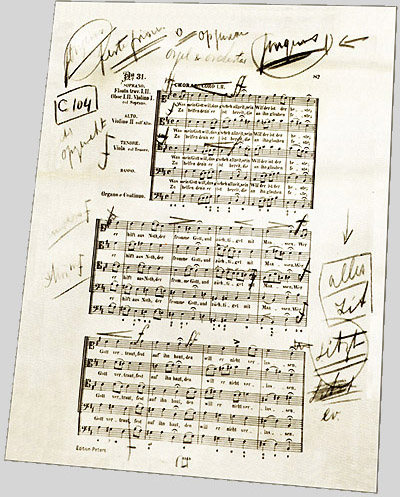

The romanticism is visually indicated by Mengelberg's strong annotations on practically every page of the score. His writings show accentuated drama alternating refined movement of melody and subtle contrasts. The baton was the important and basic instrument for the conductor. His left hand joined to add depth and nuance.

Jo Vincent - who sang in St. Matthew's Passion for the last time in a performance under Eduard van Beinum conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1953 - recalled when the Minigroove 4 LP record set was available:

After

the Germans had occupied the Netherlands in 1940, Mengelberg

continued to conduct his St. Matthew Passion on subsequent Palm

Sundays, except for the last two years of the war. He also continued

to perform for Dutch radio. And he continued recording for the Telefunken

label with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Symphony No. 3, Eroica (Beethoven)

on November 11-13, 1940, and also Symphony in C and Unfinished Symphony

(Schubert) in November 1942. When the war had started, numerous artists did not want to give up their careers. And those of the younger generation wanted to make a name for themselves and did not want to give up their freshly started careers either. When the war was over, musicians like pianist Cor de Groot (Seyss-Inquart's favorite pianist), organist Piet van Egmond, conductor Willem van Otterloo, and also composer Henk Badings (director of the 'Rijksconservatorium' in The Hague from 1941-1944), who all had been members of the Dutch 'Kulturkammer' (culture chamber), were forbidden to perform for one or more years but most of them were soon cleared of alledged misconduct. They were de-nazified.

Mengelberg had chosen not to deprive himself of what he had accomplished as a conductor. In order to be able to continue to do what he loved most, namely conducting "his" Concertgebouw Orchestra, he worked together with and for the Germans. This despite his age. In 1940 Mengelberg was 69, an age when retirement under the given circumstances would have been logical, or at least would have been wise. Mengelberg, like Wilhelm Furtwängler (who also did not understand the signs of the time entirely) and many others, did not go into exile. In the US Arturo Toscanini was number one. He had refused to conduct the fascist hymn La Giovinezza for Benito Musolini and had emigrated to the US. To go to America was apparently no option for Willem Mengelberg. He stayed in Amsterdam and secured his position. His

art was deeply rooted in the Austro-German culture. He could not deny

that this was part of his own existence. However, the question of working

together with and for the German occupier is not of an artistic nature.

The question is a moral one. How strong are you mentally. How much insight

do you have in a given political situation. How far do you go in making

use of the regulations and how far do you go in responding to the demands

of the occupier.

Right

from the beginning Mengelberg showed what his position was. Many judged

his behaviour as 'ambivalent', as he was not taking a firm stand. He

was not politically engaged and cared solely for his music business.

When in May 1940 the Netherlands were invaded by the Germans, Mengelberg

was in Germany, in Bad Gastein taking a cure and a little later he traveled

to Frankfurt. He did not see a possibility to return to Amsterdam immediately.

Sources say that he did not see the necessity to return.

He first traveled to Austria and from there, in early July, to Berlin

to participate in the festivities to commemorate Tchaikovsky's 100th

Birthday. And it was there that he recorded the famous Piano

Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 23, with pianist

This was all in stark contrast to Arturo Toscanini's attitude

who did not want to conduct his orchestra playing "Giovanezza",

the Fascist hymn, for dictator Mussolini. Toscanini left Italy for good

in 1936 to live in the USA taking his assistant, Hungarian conductor

|

Lies

the meaning of Bach's St. Matthew Passion solely in "the most beautiful

music that was ever written"? Was the appeal - as Mengelberg put it

- "die Schönste Musik die jeh geschrieben wurde"? Did the magnificent

work of J.S. Bach not relate to a deeper consciousness? Were there no

aspects of a human and also of a political nature? Jezus was the rebel,

society's critic. Was Mengelberg the servant of Caiaphas?

Right from the start of his conductorship (in 1895, when he was only 24 years of age), it became clear that the Concertgebouw Orchestra had a genius at the helm, a director who was a great organizer, a man who had an eye for detail when executing a work, planning a performance, or starting a tour, and a musician who could instantly be inspired by the score he had laid eyes on. Through the years Mengelberg became not only internationally recognized, he also was a prominent personality nationally, a celebrity who did appear every so often in magazines and newspapers. He was a star! When returning from a tour abroad and arriving at Amsterdam Central Station, newspapers would announce the arrival accompanied with a picture of the man. In magazine articles one saw Mengelberg checking the modern recording techniques, when he was a juror for a contest, or was photographed at a farewell diner just before boarding a steamer to travel to New York. Mengelberg gradually became an institution and as such played a most significant role.

What

would the orchestra have become without this important but also presumptuous

conductor who molded the institution to high standards and brought it

to world fame? It probably would have become a second rate ensemble.

|

|

Because

of his prominence he was judged more severely than other artists who

had manipulated themselves through the five years of the war.

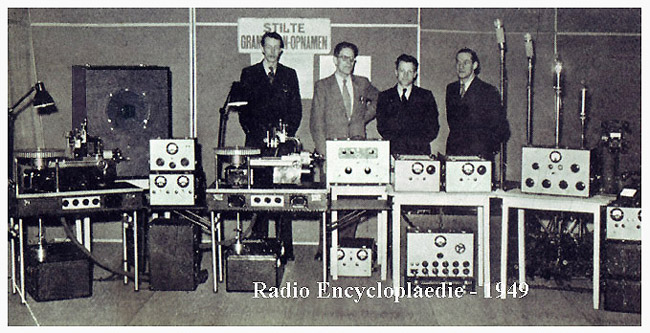

In the 1949 edition of "Radio Encyclopedie", the only entry with the name Mengelberg is of composer/ musicologist Dr. (Kurt) Rudolf Mengelberg, far cousin of the former conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Kurt Rudolf Mengelberg was artistic director of the Concertgebouw from 1925 till 1935 and general director from 1935 until 1954.) The question is also why the ideas of certain conductors, composers and instrumentalists, are often on the political right side. Maybe it is because they do not have the time to study political ideas and the evolution of society thoroughly. But most of all many tend to think only in structured music, of ideas organized in sound, in which for them there is no place for external influences. This is applicable for the purely classically oriented musicians. Those who roamed the realm of modernistic and avantgarde music styles generally are of the rebellious type. Willem

Mengelberg's behavior had not only become problematic to the Dutch music

scene but also to the entire nation. In 1945 he was declared unworthy

to keep his post of principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

This verdict became definitive in 1947, the year in which bans on several

other prominent people with questionable behavior during the war were

lifted. (In Germany prominent Wilhelm Furtwangler was allowed to perform

again in 1947.) The Dutch government did not have an eye for gray tones but only could see black and white at the time and the leaders announced that Eduard van Beinum was to be principal conductor of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. Mengelberg spent the remainder of his life in exile, in Switzerland, in his chalet, Chasa Mengelberg, Hof Zuort, Graubünden. In 1950 Mr. Michael Thomas of the Cherubini Society in London corresponded with the conductor and proposed making new recordings. On August 14th, 1950, Mengelberg wrote:

Dutch composer, musicologist and journalist Wouter Paap (1908-1981) is the author of a small but comprehensive 80 page illustrated biography of Willem Mengelberg, published by Elsevier Company. The book was written in conjunction with the Mengelberg Documenta Musicae LP series, issued by Philips' Phonografische Industrie in 1960. The book included a 7 inch 45 RPM disc with the performance by Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra of 'Oud Nederlandse Dansen' (Old Dutch Dances) composed by Julius Röntgen. On the last pages Paap recounts that on the day Willem Mengelberg would have been 80, March 22nd, his actual birthday, farmers of Zuort had put his body on a sleigh and brought him on the snowy path to the valley while bells were ringing in the mountains in honor and mourn. In the Hofkirche in Lucerne the Funeral Mass of Dutch composer Johannes Verhulst was performed. Ferdinand Helman, former concert master of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, played the Second Movement from Bach's Violin Concerto.

On the afternoon of Saturday, March 31st, 1951, a concert was given in memory of Willem Mengelberg by the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Otto Klemperer. The program of this memorial concert was well chosen. It opened with Mozart's Maurerische Trauermusik (Masonic Funeral Music). Then Dutch contralto Roos Boelsma was soloist in "Der Abschied" (The Farewell), the last song from Das Lied von der Erde (Song of the Earth) of Gustav Mahler. The Amsterdam Toonkunstkoor sang the Choral "Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden" (When I must depart one day) from St. Matthew Passion. The last work on the program was Beethoven's 3rd Symphony, Eroica, with the marcia funebre. It is true, Mengelberg led an intense and heroic life that he spent in the service of music - and despite mistakes and error of judgement - in the service of humanity.

The

List of Mengelberg. This is the title of a documentary film

made by cinematographer Advertisement Click on the Image for More Info

|

Apart

from the wire recorder, the tape recorder and the direct-to-disc

recording system (as it generally was used in the days of 78 RPM

before the tape recorder made the LP possible already in 1947, but launched

in 1948), there is another medium for sound recording that has been

widely used. That medium is celluloid film as it is used in the film

industry. The sound track is a narrow strip on one side of the images

on the 35 mm (and also on the 16 mm) celluloid film. The track is a

photographic track, read by a photocell.

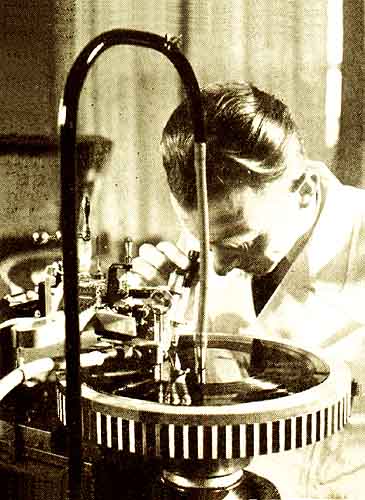

The

Philips Miller sound recording system however had a different way of

recording and had its own specifications.

The speed of the film is 32 cm/sec. (12.56 inch per second.). The reading of the track is done the same way as with the optical soundtrack of a movie. The Philimil film passes along a narrow slot with a lamp on

one

side of the film and the variations in the signal are read by a photocell

on the other side and then translated into sound. Editing

of the recorded Philips-Miller film by means of splicing was possible

and thus mistakes could be corrected by eliminating or replacing them

by bits of other takes. Since the film did not need developing, the

recording could be played back instantly on the spot. |

The restoration of the 8000 meter film and the transfer to tape were a painstaking operation. Attention had to be paid to keep the black top layer intact. Furthermore a constant playback speed should be maintained throughout. And dropouts caused by erosion or mishandling of the black top layer should be eliminated. This could be done of course after the transfer to magnetic tape had been made and the advantage of the tape recorder could come fully into service by copying, replacing and inserting bits of tape, in one word: splicing. Fortunately various Philips-Miller systems were still in use in the beginning of the nineteen fifties. The final magnetic tape became the master from which the matrixes were cut and the records were pressed on the Philips Minigroove label in 1953.

Some sources on the Internet mentioned that Mengelberg's St. Matthew Passion was issued earlier on 78 RPM records before the release on LP in 1953. And they maintained that the shellac discs had been the basis for the Philips Minigroove 4 LP set. This of course is not the case. These recordings were not made in 1939 for immediate commercial release as "N.V. Philips' Gloeilampenfabrieken" in Eindhoven did not have established a record label yet. Plans for a record division were certainly in the pipeline but a commercial realization was obviously obstructed by the outbreak of World War Two.

It

was a few years later, in 1942, that "N.V. Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken"

in Eindhoven acquired "Hollandsche Decca Distributie"

(Dutch Decca Distribution). It was a small factory located above

a laundry in the city of Amsterdam. This production facility was later

to be the basis for the Philips label. (Note: The acquisition also explains

the collaboration between Philips and English Decca, and finally the

acquisition of the Decca label by Phonogram as the company was named

in the nineteen sixties). Despite the 1942 purchase, a release

of the Mengelberg recording could only be materialized many years later

when the Long Playing record had become the medium and after Philips'

Phonographische Industrie had been founded in 1950. And of course

when the Miller films had surfaced.

There

is another noteworthy aspect of the Philips recording of St. Matthew's

Passion. In those days the concerts given in the Concertgebouw were

broadcast at regular intervals. This custom was ended in the early nineteen

eighties. Before the war the performances were captured with just one

microphone hanging slightly in front of and several feet above the orchestra.

(So Bob Fine's One

microphone with a cardioid characteristic is used. It captures very

well the musicians in the orchestra, but is not sensitive in the direction

of the audience. No phase shifting took place which occurs when various

microphones are being used and placed near groups of instruments in

the orchestra at various distances to highlight these instruments for

clarity. But that practice can easily change the natural sound balance

of the orchestra and the harmonious character of the instruments (as

is already more or less the case in early

When listening to the "one microphone recording", the instruments, singers and choruses are placed in a natural perspective, exactly as they were positioned on the stage of the Concertgebouw's main hall with its beautiful acoustics. Us (short for Marius) van der Meulen recorded Mengelberg's St. Matthew performance in 1939. He did join Philips Phonografische Industrie in 1950 when the Philips label started and the first recordings were made with conductors Willem van Otterloo, Paul van Kempen and Antal Dorati, with pianists Clara Haskil, Cor de Groot, Alexander Uninsky, Abbey Simon, Eduardo del Puyo and Theo van der Pas, with violinists Herman Krebbers and Theo Olof, with singers Jo Vincent and Gré Brouwenstijn, and other artists who made the Philips classical label famous at home and abroad. (Note: Eduard van Beinum had a long standing contract with English Decca. He joined the Philips label only much later, in 1956.) Marius van der Meulen is well known and admired for the Philips Bach project with harpsichordist Isolde Ahlgrimm.)

Some 8 years after the first release on LP this historic performance with Mengelberg was re-released in a new transfer when tape heads and amplifiers had gained in dynamic capability and when the filtering and the editing technique certainly had been improved, and when the cutting process and the production of matrixes had been improved significantly. But then the producers of Philips' Phonographische Industrie thought it appropriate to leave out the ticks of the baton at the beginning of the performance which were so characteristic of Willem Mengelberg.

Because

of the existence of CD, DVD and SACD, a significant aspect of optical

signal reading is the obvious absence of the mechanical contact of tape

and tape heads and of the stylus and the groove in the vinyl disc. If

one compares the recording of 'St. Matthew Passion' to the recordings

of other historic performances made with 78 RPM acetates, one can easily

hear that the recording of 'St. Matthew Passion' was done using the

Philips Miller audio recording system and thus does not show the "mechanical

quality" of acetates.

If

the old Philips-Miller machines would still exist and could be restored,

and if the technicians could transcribe the films once again, it would

be possible to transfer the sound captured on the Philimil film directly

to a high resolution digital format (DVD or double layer SACD) after

which the restoration of the signal and the editing could take place

in the digital domain. That would mean the complete elimination of the

intermediate magnetic sound recording tape and its anomalies, and it

would mean that the authenticity of the performance could be heightened

further. This of course would only be true if the CD transfer of the

magnetic tape on the current Philips CD edition showed that the result

of the totally optical transfer was superior. |

|

LP

RELEASES AND REISSUES

|

|

|

|

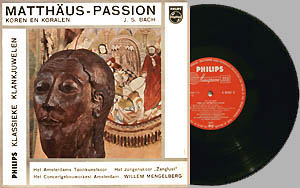

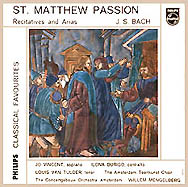

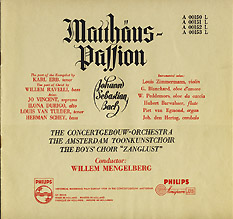

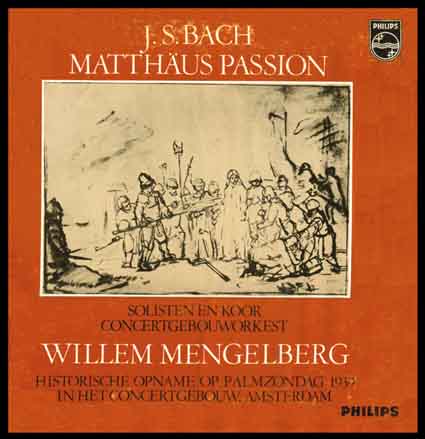

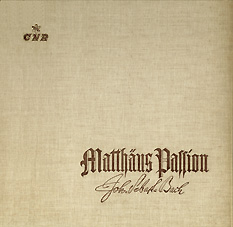

Bach's 'Matthäus Passion' conducted by Willem Mengelberg. The famous live performance on Palm Sunday 1939 Singers: Instrumentalists: Toonkunstkoor,

Original booklet of the first release. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

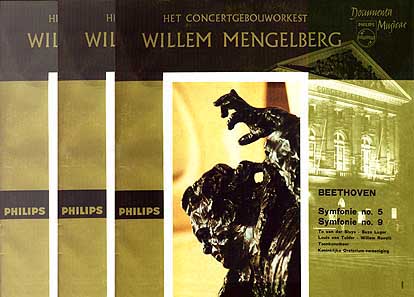

Documenta

Musicae Discography |

|

In the series of the live performances for AVRO Radio Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 was damaged. The 3rd was later included in the LP box containing all of Beethoven's Symphonies (Philips 6767 003) when Teldec made their recording of the Third Symphony available.

Many recordings made in Amsterdam, Berlin and New York have been edited and released on CD. There are various chapters of the "Willem Mengelberg Society" where more details can be obtained by subscribing to a newsletter. |

|

The series Documenta Musicae was a project of former conductor, the late Otto Glastra-Van Loon who was responsible for building a classical catalogue right from the beginning of the existence of the Philips label in 1950. Even though the Philips Miller Sound Recording System was in use by the Dutch Radio Authority, performances of the Concertgebouw Orchestra which were broadcast by AVRO Radio (Algemene Vereniging Radio Omroep) in Hilversum, the Netherlands in the 1930 and 1940s were cut on two-sided acetate discs playing at 78 RPM. So were the many Symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, Franck and Schubert, conducted by Willem Mengelberg, as listed above. As

an example, shown above, a few acetate discs (glass covered with a layer

of lacquer), not of Willem Mengelberg but of Eduard van Beinum conducting

the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Dvorak's Serenade for Wind Instruments,

Violin and Bass, Slavonic Dances Op. 46, Nos. 1 and 8, Overture "In

Nature", and Dvorak's Mazurek in E minor for Violin and Orchestra

with violinist Frans Vonk. (His son was the late conductor Hans

Vonk - 1942-2004). These

recordings of works of Antonin Dvorak were made on the 11th of September,

1941, by AVRO Radio, no public was present. |

|

|

|

|

The

Amsterdam Concertgebouw on a Postcard from the 1960s. And below a photograph

taken in 2011. The Concertgebouw was completely restored in the 1980s,

inside and outside, and reopened in 1988.

|

This page, first published on the internet in 2001, is an elaboration of an article written in 1995.

Home | Audio & Music Bulletin | LP List | Record Cleaning Page

|

Rudolf A. Bruil and co-authors |

The

press conference was organized by 'Philips' Phonographische Industrie'

(PPI), the Dutch record company that was founded two and a half years

earlier, in September of 1950.

The

press conference was organized by 'Philips' Phonographische Industrie'

(PPI), the Dutch record company that was founded two and a half years

earlier, in September of 1950.

Willem

Mengelberg however wrote letters addressed to the occupier, expressing

his thanks for this or that arrangement, for a specific supply, or for

an important financial contribution. Willem Mengelberg was allowed

to travel. He and pianist Cor De Groot - who was in his early

twenties - traveled to Salzburg to perform at the Salzburger Festspiele

(Salzburg Festival). There, on August 16, 1942, Cor De Groot was the

soloist in Beethoven's Emperor Concerto (No. 5 Op. 73). Mengelberg was

even allowed to travel to Spain and Portugal, as Dutch journalist Dick

Verkijk mentions in his extensive well-researched documentation

about the behaviour of many an important influential Dutch person during

the German occupation published in "Radio Hilversum 1940-1945"

(Amsterdam, 1974), while others had to follow difficult tracks, sometimes

via Switzerland and through the Pyrenean Mountains, in order to reach

Spain. For those this was the only way to avoid execution, the only

way to finally reach England and to report to the government in exile,

or to join the Allied Forces eventually. Cor de Groot also performed

in Riga (Latvia). And in April, 1942, the entire Concertgebouw Orchestra

with Willem Mengelberg and again Cor De Groot traveled to Vienna to

celebrate the centenary of the Wiener Philharmoniker (March 1942). Cor

De Groot was the soloist in Variations Symphoniques (César Franck),

Mengelberg conducting. After the war it was argued that Cor de Groot,

by accepting many privileges and "collaborating" with the

German occupier, was able to protect the lives of two people important

to his relatives.

Willem

Mengelberg however wrote letters addressed to the occupier, expressing

his thanks for this or that arrangement, for a specific supply, or for

an important financial contribution. Willem Mengelberg was allowed

to travel. He and pianist Cor De Groot - who was in his early

twenties - traveled to Salzburg to perform at the Salzburger Festspiele

(Salzburg Festival). There, on August 16, 1942, Cor De Groot was the

soloist in Beethoven's Emperor Concerto (No. 5 Op. 73). Mengelberg was

even allowed to travel to Spain and Portugal, as Dutch journalist Dick

Verkijk mentions in his extensive well-researched documentation

about the behaviour of many an important influential Dutch person during

the German occupation published in "Radio Hilversum 1940-1945"

(Amsterdam, 1974), while others had to follow difficult tracks, sometimes

via Switzerland and through the Pyrenean Mountains, in order to reach

Spain. For those this was the only way to avoid execution, the only

way to finally reach England and to report to the government in exile,

or to join the Allied Forces eventually. Cor de Groot also performed

in Riga (Latvia). And in April, 1942, the entire Concertgebouw Orchestra

with Willem Mengelberg and again Cor De Groot traveled to Vienna to

celebrate the centenary of the Wiener Philharmoniker (March 1942). Cor

De Groot was the soloist in Variations Symphoniques (César Franck),

Mengelberg conducting. After the war it was argued that Cor de Groot,

by accepting many privileges and "collaborating" with the

German occupier, was able to protect the lives of two people important

to his relatives.

There

were many performers, composers and artists, who did not want to become

a member of the Reichsmusikkammer, the music section of the "Reichskulturkammer"

(Chamber of Culture), the institution which set the rules for performances

and stipulated what material could be performed and what was "denatured

art" (Entartete Kunst). Those who did not want to join were

not allowed to perform and could hardly earn a living. (Nevertheless

the Germans were sabotaged time and time again and the "Kulturkammer"

never had a firm grip on the artistic life in the Netherlands.)

There

were many performers, composers and artists, who did not want to become

a member of the Reichsmusikkammer, the music section of the "Reichskulturkammer"

(Chamber of Culture), the institution which set the rules for performances

and stipulated what material could be performed and what was "denatured

art" (Entartete Kunst). Those who did not want to join were

not allowed to perform and could hardly earn a living. (Nevertheless

the Germans were sabotaged time and time again and the "Kulturkammer"

never had a firm grip on the artistic life in the Netherlands.)

The

"near future" was very short for a man his age. And it is

suspected that Mr. Johan Koning did not want to burn his fingers on

the possibility of making recordings by Willem Mengelberg and used the

contract as a pretext. Mengelberg died 6 months later on March 22nd,

1951, in Switzerland. That was in fact two years before the presentation

in 1953 of the sound recording of the 1939 performance of Bach's St.

Matthew Passion.

The

"near future" was very short for a man his age. And it is

suspected that Mr. Johan Koning did not want to burn his fingers on

the possibility of making recordings by Willem Mengelberg and used the

contract as a pretext. Mengelberg died 6 months later on March 22nd,

1951, in Switzerland. That was in fact two years before the presentation

in 1953 of the sound recording of the 1939 performance of Bach's St.

Matthew Passion.

The

Philips Miller sound recording system was used by various radio stations

like the BBC and the Dutch Radio Broadcasting Union (Nederlandse

Radio Unie) well into the nineteen forties and early fifties, and it

was also used by the technicians of the Philips laboratory in Eindhoven.

It is on this sound film that Willem Mengelberg's famous performance

of 'St. Matthew Passion' (BWV 244) on Palm Sunday 1939 was recorded.

It was not a recording by AVRO radio but by engineers of Philips in

Eindhoven as is stated in "Discografie van het Concertgebouworkest"

(Discography of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, 1989), entry 39-2 April.

The films were considered to be lost or even non existent until they

were found in a damp cellar. The importance of these recordings was

immediately recognized by Philips in Eindhoven. In 1952 the recordings

were handed over to their subsidiary 'Philips Phonografische Industrie'

after they were carefully restored and could be transcribed to LP.

The

Philips Miller sound recording system was used by various radio stations

like the BBC and the Dutch Radio Broadcasting Union (Nederlandse

Radio Unie) well into the nineteen forties and early fifties, and it

was also used by the technicians of the Philips laboratory in Eindhoven.

It is on this sound film that Willem Mengelberg's famous performance

of 'St. Matthew Passion' (BWV 244) on Palm Sunday 1939 was recorded.

It was not a recording by AVRO radio but by engineers of Philips in

Eindhoven as is stated in "Discografie van het Concertgebouworkest"

(Discography of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, 1989), entry 39-2 April.

The films were considered to be lost or even non existent until they

were found in a damp cellar. The importance of these recordings was

immediately recognized by Philips in Eindhoven. In 1952 the recordings

were handed over to their subsidiary 'Philips Phonografische Industrie'

after they were carefully restored and could be transcribed to LP.